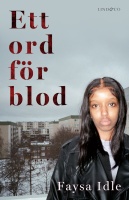

Ett ord för blod (A Word for Blood) tells the same story as Tills alla dör by Diamant Salihu, but from the perspective of someone whose family is involved in the brutal gang war.

Ett ord för blod

Faysa Idle, Theodor Lundgren and Daniel Fridell

ISBN: 9789180185844

Lind & Co, 2023-09-06

Swedish

Idle does an excellent job of describing the events of the gang war from the perspective of someone whose family is involved and to the extent she can the thoughts and motivations of those involved. As a recipe for a solution this book falls flat, but as a piece of the puzzle, the book shines. (5/5)

Or rather, Faysa's brother "Bilal"[1] is involved. The rest are along for the ride.

Bilal is, in Idle's words, "a thrill seeker", and was attracted to a criminal lifestyle from early years. It was he who abused his sister's admiration, by making her his first accomplice and by teaching her to hide his money and other evidence if the police were to show up. Faysa then has her own criminal career, starting with shoplifting and continuing with burglary. But while her brother becomes a leading figure in the organized crime world, she is not really seen as a criminal - Bilal even chews her out, saying that "you're not a criminal"[2] - nor is she exposed to the danger that her brother is. Women, as Idle repeatedly tell us, are protected in the culture of organized crime[3], letting her observe events from the inside without running the risk of getting murdered.

She does an excellent job of describing the events and to the extent she can the thoughts and motivations of those involved. Sometimes, as I'll argue below, she does so inadvertently. This is a great book, and yes, you'll have insights into the gang war and the environment it takes place in. Idle has a way with words, and while the jury in my head still is out on whether it is good or bad to mix in street style language in a book, it works. It gives the work a flavor of being written by someone who has been there, but like most people who will read it, I can't really tell the difference between authentic street speak and someone just faking it. (I grew up in nearby Husby and I don't speak like that because, well, I'm educated.) Her style is clear, straight and to the point. So much, in fact, that it's glaringly obvious what she avoids, and we'll get to that.

While the book is an autobiography, it's inevitable that people will look to it for solutions or clues to the continuously unfolding atrocity that is happening. The book provides little in the way of a recipe for a solution other than "fix things": she lists pour in billions of kronor, fix segregation once and for all, education, jobs, families

[4], and that's it. The fact that the government has tried exactly that - poured in billions of kronor, only to find that they could barely move the needle on the problems of segregation, education, jobs and families - seems to have passed her by. As a solution this book falls flat, and that's perhaps why Idle avoids trying to present one.

As a piece of the puzzle, however, the book shines. When putting this book side by side with Tills alla dör a fairly clear picture emerges. I'd summarize it as "family, state, culture", and let's start with the first two before digging into the third:

Family: Idle describes her upbringing in what I'd call a "weak family" - one where the parents are unable to provide enough parenting to create a functioning family unit and keep the kids on track. Faysa's father has another family in Kenya, so she and her five siblings are left in Tensta with her mother, who quite understandably are overwhelmed by caring for six children. Note that by "weak" I don't mean "without rules" - Faysa grows up with the ever present threat of violence from her older brother for minor infractions of the many rules she's expected to follow. What I mean is the failure to create a context involving the parents that the children can identify with and want to be part of, provides for their needs, and guides them to become well-adjusted members of society.[5]

State: In theory the Swedish state "just works" for everyone. In practice, it's unintentionally very optimized toward a specific type of citizen; one whose family has lived in it for generations and where the person and their family is more a product of the state than the state is a product of them. This adds to the difficulties when a family that was formed by very different forces tries to live here. In theory the robust Swedish welfare state should step in when the family fails. In practice, the complexities have proven too much. But what are these "optimizations" then? In particular I want to call out the fact that the educational system expects children to speak Swedish fluently in order to absorb knowledge via books at a high enough rate to make it through school in nine years.

When both family and state can't do the job the kids end up being raised by the ambient culture they inhabit, and boy is that one a nanny from Hell. It has been described as "Swedish entitlement culture meets MENA honor culture and becomes resentful nihilistic gangster culture", and to give a couple of examples of what has become normalized:

-

While in school Faysa shoplifts and sells candy to other pupils. This is of course something that gives her a high social status in school.

-

Faysa instigates a burglary and describes her feelings after getting money for the laptops they stole as

Damn, I had made something. Something all my own.

[6], and her friends cheer her on. -

When she remains quiet under interrogation by police for the burglary (and is not prosecuted for it) her status among her peers skyrocket.[7]

-

Two brothers are described as "having done a bit of mischief"[8]. Tills alla dör is more specific - one committed violent robbery (beat up a girl to steal her purse) and both have committed burglary.

-

Kids play "gang war" where they shoot at each other with pretend guns.[9]

I can go on, but you get the gist: anti-social behavior is cool among the young, and not just in a small clique. That's the culture.

What more stands out is what isn't in the book: any concern for the victims and any deeper insight into her own place. In Faysa's world there are those who do things - gangsters - and those who don't - their victims, where the former matter and the latter don't.

If the gangsters and their families and friends matter, to the extent that they're worth mentioning and their feelings acknowledged, the victims of those actions that are outside the group are just background noise. What about the homeowners who came home to find someone had taken their laptops? Not even worth mentioning. Store owners getting robbed? Everyone afraid to testify? Idle mentions people who had fought to live in peace

, but seems oblivious to the amount of distress she herself has helped deliver to them. When she lists who are the victims of the gangsters's way of playing with people's lives

she only list their families[10]. This is a thread throughout the book - the impact of her and her peers on individuals and society as a whole is never really acknowledged. When describing the trauma experienced by the people living in Tensta in the aftermath of the twin murder at Mynta[11], she states that The whole suburb was boiling. You could almost hear the cries for revenge bounce between the concrete houses

. Really? The "whole suburb"? All 17,000 of them? The people who had fought to live in peace

that are mentioned two paragraphs down want bloody revenge? It's impossible to not conclude that "the whole suburb" was Faysa and her peers - roughly 100 people maybe at most. But the rest, as we said, don't matter.

At the end of the book Idle describes herself as having been codependent. Her whole family got dragged along into Bilal's criminal life, but they never told him to stop. When reading the book, I can't help but think that she's - inadvertently - pulling the same stunt on us. Yes, she burglarized a house - but it's the fault of society, it's our fault. Yes, what she did was incredibly destructive to society, but it's society's fault all the same.

"It's your fault that I'm abusing you."

That's the culture.

With that out of the way let's look at the codependency of Swedish culture outside of Tensta. Ignoring the aspects of it as psychological warfare aimed at opponents[12], Idle aptly describes gangster rap as an industry where the violence becomes a theater stage for those not living there. I'd argue that it's not just gangster rap, the whole rise in crime has become a kind of "Swedish noir" theater for those not directly involved. The actors have artist names to make them both more and less human: "Ayye", "Makelele", "Captain", "Musse", "Poy", and so on. Much like superheroes in movies there's an endless stream of them[c], and they come, play their role, then get killed off or just disappear. They have dehumanized themselves as a side effect, and I think this has contributed to the general denial with which Swedish society has reacted to the growth of organized crime.