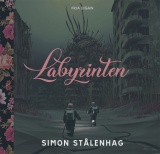

The Labyrinth was for many a departure from Stålenhag's usual style. This time, the world is really ending, and the horror is not something that is under the surface - quite the opposite, the remnants of humanity hide in underground shelters and the world is covered in ashes and the remains of those who didn't make it to the shelters.

ISBN: 9789189143012

Fria Ligan, 2020-12-09

Swedish and English

- Editions

- The Labyrinth

English edition

ISBN: 9781398509993

Simon and Schuster, 2021-10-28

- The Labyrinth

It doesn't really dig into the central moral dilemma underlying the survivors's guilt, and the storytelling is like The Electric State where it alludes and hints but doesn't really deliver. Except on the last page, where Stålenhag manages to scuttle pretty much his whole worldbuilding. That's a delivery of sorts I guess. (3/5)

Coming at the end of the Year of Covid, it's certainly possible to draw parallels to the epidemic, but that would require Stålenhag to predict it back in May 2018 when he started posting the first paintings[a] from The Labyrinth. Since his previous book The Electric State was released in 2017, I think at least some inspiration for The Labyrinth is from the Syrian refugee crisis of 2015 - 2016.

The central question of the book, what we are willing to do as a society in order to survive, is something that doesn't have an answer and the book doesn't provide one. When dealing with extreme situations we have, to some extent, left the domain of our morals[b]. The only thing the survivors can be sure of is that "we survived, and they did not".

Art-wise this is a weaker book than The Electric State, with many sequences essentially being the same scene with the characters moving around. There are some '90s objects - thermoses and phones and chairs - that anyone who lived in Sweden during that decade will immediately recognize, but they don't really matter because the fictional world could be anywhere, at any time. This means the book has to stand on its own without relying on Swedish generation X nostalgia, and it doesn't really do that.

It doesn't really dig into the moral dilemma, and like The Electric State it alludes and hints and waves its hands but doesn't really deliver. Which is a serious miss since Stålenhag actually experienced the societal impact of the refugee crisis first hand, and certainly has political views and opinions.

Then, on the last page, Stålenhag manages to scuttle pretty much his whole worldbuilding. That's a delivery of sorts I guess.